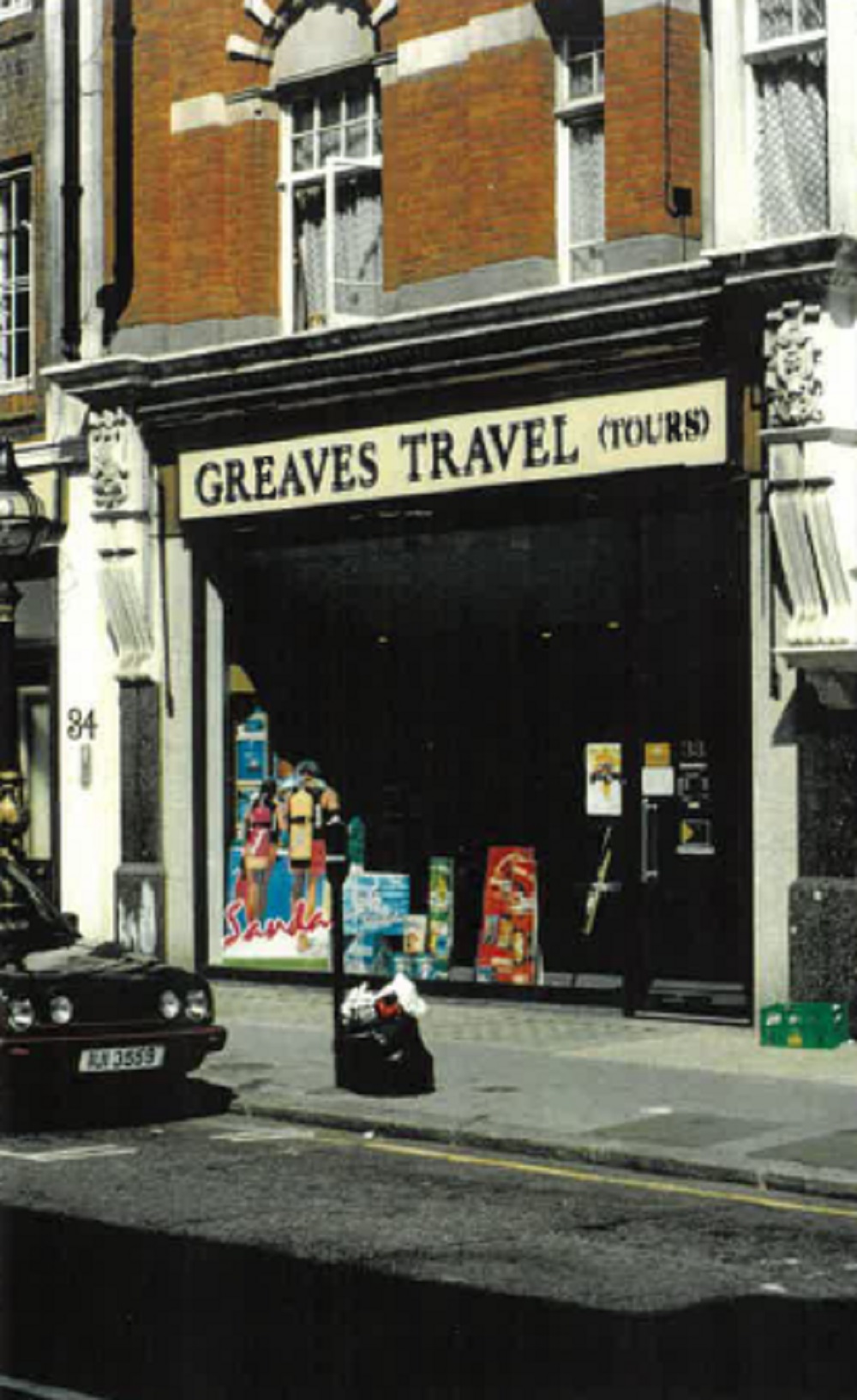

Marylebone High Street didn’t always boast the elegant variety of boutiques, cafés and small retailers that it does today. There was a time when shops were empty and of those that weren’t, several were occupied by charities. Perhaps most shockingly of all for today’s trendy locals, some of the local pubs even had plastic chairs outside.

But that was almost 30 years ago. Now the high street is very different, with the Howard de Walden Estate, which owns 95 acres of land in and around Marylebone, having invested hundreds of millions of pounds upgrading its acreage.

Since 1997, Shirin Elghanayan, the top retail leasing agent in London for CBRE, the property services group, has been helping the Howard de Walden Estate to find tenants for the dozens of shops that line the high street. The thoroughfare had been “not in a good way. It felt like the street had lost direction. There were something like eighteen charity shops, six or seven vacant shops. There were shops selling rugs that spilled on to the street. It was not very nice.”

The Howard de Walden family pushed for the area’s rejuvenation. At present it is led by Peter Czernin, 58, who became Baron Howard de Walden last year after the death of his mother, Hazel, but there are many more aunts, uncles and cousins. Last year they received £50 million of dividends.

The estate, now valued at £4.5 billion, traces its history to the Domesday Book in 1086 and is one of the great aristocratic landowning estates in London, along with Grosvenor and Cadogan. The high street runs through the heart of the estate, although Harley Street, the destination for upmarket dentists and surgeons, is more famous. The family has controlled the estate since 1879, when the death of the childless fifth Duke of Portland resulted in the land being passed to his sister, Lucy Joan Bentinck, widow of the sixth Baron Howard de Walden.

“When the high street was not in a good way and we were trying to attract some really cool retailers, we went and knocked on many doors, asking [businesses] if they would consider [opening] a shop here,” Elghanayan said. In the first couple of years, the estate did a lot of “soft” deals, cutting rents to lure the businesses it wanted in the area. One of Elghanayan’s first coups was getting Conran, Sir Terence Conran’s department store, into No 55, at the northern end of the high street, not far from Madame Tussauds.

Another milestone came in 1999, when a derelict post office on the corner of Weymouth Street, about halfway down the high street, was refurbished and let to Aveda, the “lifestyle salon and spa”. Agnès b, the French fashion designer, opened her Marylebone shop that year and others soon followed.

“It was never about opening one store in isolation. We were selling a dream that Marylebone High Street was at a turning point and its revival was something brands wanted to be a part of. Some of the brands that set Marylebone apart, including La Fromagerie, Daunt Books, Ginger Pig and Cologne & Cotton, are still the beating heart of the street today.”

The expectation was that, by getting the right mix of businesses to move in, the area would become more popular and that eventually rents would catch up. In 2005, the average rent on Marylebone High Street was about £135 per sq ft per year; it is now up to £400 per sq ft, although that is still a little off the £415 per sq ft that Howard de Walden was achieving just before the pandemic.

Rob Kirk, head of retail and leisure at Howard de Walden, is certain that the estate can surpass the pre-pandemic record. Some of the buildings down the street owned by other landlords are fetching upwards of £500 per sq ft in rent, but Kirk and his team are fussier about who they let in.

“Take the [now-closed] Lloyds [Bank] building,” he said. “There have been three brands who’ve been under offer, all of which we’ve said ‘no’ to. These are great global brands and a lot of places would be very happy to accept them. They’re just not right, in our view, for our high street.”

Similarly, when Le Pain Quotidien went into administration last year, Howard de Walden got the building back for the first time in almost three decades. Smaller landlords might have rushed to fill it again with whichever business offered the most money, but the estate is under less pressure to generate an immediate return.

Instead, Kirk and his team are refurbishing the site and will wait until they find a suitable replacement. Any new tenant must be a café that sells pastries and coffee, but not a chain and not a restaurant. It is seen as “a trickier site” because it is quite big and therefore expensive, possibly taking it out of the reach of small, independent coffee shops and bakeries. “It’s just a balance, but we’ll hold out until we get close to the right person.”

Whoever comes in, they will not be on a 25-year lease of the kind that was the norm in the 1990s. A ten-year lease is much more common now. “We know there will be trends and they may change.[Shorter leases] help to keep the street fresh,” Elghanayan said.

Howard de Walden would like to add more handbag brands to the high street, as well as more menswear shops and perhaps another homewares store or two, given that Conran left for Clerkenwell in May. As ever, there will be a strict criteria for any new tenants. The estate has even been known to ask occupiers to change the name of their stores if it does not fit in with the feel of the area. It is unashamedly finicky, but the approach has worked.

“[The high street’s] remarkable success has had a profound impact on the entire estate,” Elghanayan said. “Creating a tenant mix that truly serves the consumer is the foundation for a successful high street, not focusing solely on the highest rents. Once you get the mix right, the rents always follow organically. Our rents could be double what they are, but then it would be a very different street.”